Pupils in Hampshire achieved A-level results close to the regional average in the South East, new figures show.

Across England, the average point score for 2022-23 was lower than the previous academic year, which was expected due to a return to pre-pandemic grading, but results saw an increase compared to 2018-19.

However, experts said the Government has failed to invest sufficiently in education recovery following the pandemic and must address the teacher recruitment and retention crisis.

Department for Education figures show the average A-level score achieved by pupils in Hampshire was 35.1 out of 60 maximum points – almost in line with the result in the South East as a whole, where youngsters averaged 34.9 points.

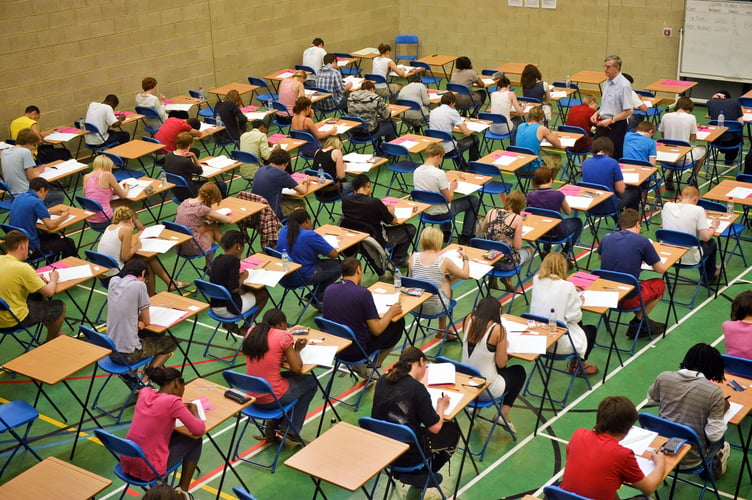

Of the 8,701 students who took A-levels at state-funded Hampshire schools and colleges, 14% achieved three A* or A grades, 23.8% received AAB or better and 85.2% got at least two A-levels.

With the return to the pre-pandemic grading system, pupils’ average result across the country was 34 – a decrease from 37.7 in 2021-22, but 1.4 points more than in 2018-19, the last full school year before schools moved to online teaching.

Sarah Hannafin, head of policy at school leaders’ union NAHT, said: “It is vital that everyone remembers that we cannot compare this year’s results with those from previous years.

“The student cohort, the context and the approach to grading has been different every year since 2019 so simplistic comparisons are unhelpful and will not tell the full story of the experiences of students or their schools and colleges.”

Meanwhile, the gap between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged students in England stood at 4.9 points, with average scores of 34.7 and 29.8 points, respectively.

The same was true for Hampshire, where those better-off received 35.4 points, while their peers from disadvantaged backgrounds scored 30.6 points.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said: “Disadvantaged students do less well in A-levels than other students and are less likely to study for A-levels in the first place.

“The Government has failed to invest sufficiently in education recovery following the pandemic and in schools and colleges in general.

“Policy-makers must improve funding rates, address the teacher recruitment and retention crisis, make the inspection system less punitive and more supportive, and put an end to child poverty.”

Mrs Hannafin added: “Services like social care and mental health support for young people have also been hugely under-funded over the last decade, and where issues in their lives are not identified and addressed this also affects their learning.

“All this must change if the Government is serious about closing the disadvantage gap.”

A Department for Education spokesperson: “We want to make sure that all young people have the same opportunities they need to succeed.

“Before the pandemic, we closed the disadvantage gap by more than 9% – demonstrating that our policies and programmes can make a big impact.

“We are continuing this work through our Recovery Premium, National Tutoring Programme, and the 16-19 Tuition Fund – all of which are focused on helping the most disadvantaged catch up and get ahead with their education.”